June 18, 2015

Under Pennsylvania law, the “gist of the action” doctrine supplies a useful defense by which a defendant can prevent a plaintiff from invoking tort principles in an ordinary breach of contract case. Because the defense is both fact-specific and doctrinally ambiguous, however, it has generated considerable litigation over the years. Two recent decisions are of particular interest in illustrating the current contours of the doctrine, and in framing the issues that courts will continue to face when applying it.

In the first decision, Bruno v. Erie Ins. Co., 106 A.3d 48, 50 (Pa. Dec. 15, 2014), the Pennsylvania Supreme Court finally weighed in on the doctrine. In essence, the Supreme Court adopted the Superior Court’s approach in Bash v. Bell Tel., 411 Pa. Super. 347, 601 A.2d 825 (1992) – i.e., treating the central analytical question as whether the duty alleged was imposed by the parties’ agreement, or by law as a matter of social policy.

The Brunos had argued, in addition, that another prior Superior Court decision, eToll Inc. v. Elias/Savion Adver., 811 A.2d 10, 21 (Pa. Super. 2002), should be expressly repudiated as “wrongly decided” to the extent eToll dismissed tort claims on the grounds they were “inextricably intertwined” with the parties’ contractual relationship. Although the Supreme Court did not so reject eToll, it did, however, ultimately rule in favor of the Brunos by reinstating their claim that an insurance adjuster’s erroneous assurance that the Brunos’ household mold infestation was “harmless” arose in tort rather than in contract. The facts that the parties had been brought together by a contract, and that the negligent act arose in the performance of a contractual duty, were not enough to dismiss the separate tort claim.

Although the Bruno holding may have made some defendants’ spirits sink – because it allowed tort claims arising from a contractual relationship – defendants may take heart in a second decision that recently followed Bruno. In Certainteed Ceilings Corp. v. Aiken, 2015 WL 410029 (E.D. Pa. Jan. 29, 2015), Judge Baylson took a dimmer view of a plaintiff’s tort claims. He was considering a complaint in which an employer sued a former employee, both in contract for breach of a confidentiality agreement, and also in tort for breach of fiduciary duty arising from the disclosure of confidential information.

After surveying Bruno and other cases addressing the gist of the action doctrine, the court found that cases analyzing fiduciary duty claims under the doctrine could be grouped into two categories: (1) fiduciary duty claims that go beyond the “particular obligations” contained in the parties’ contract, which are not barred, versus (2) fiduciary duty claims that do not “transcend or exist outside of” the parties’ contract, which are barred.

Against this backdrop, Judge Baylson concluded that the employer’s tort claim must be dismissed because it was “inextricably tied to the terms” of the confidentiality agreement and, thus, “essentially duplicates a breach of contract claim.” In so holding, the district court’s reasoning sounded echoes of eToll’s “inextricably intertwined” analysis – the same analysis that the Brunos had criticized before the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Judge Baylson’s approach was also consistent with the concurring opinion of Justices Eakin and Castille, in Bruno, which had signaled their view that both the doctrine itself, and perhaps its eToll formulation specifically, remain important tools for keeping tort principles out of contract cases.

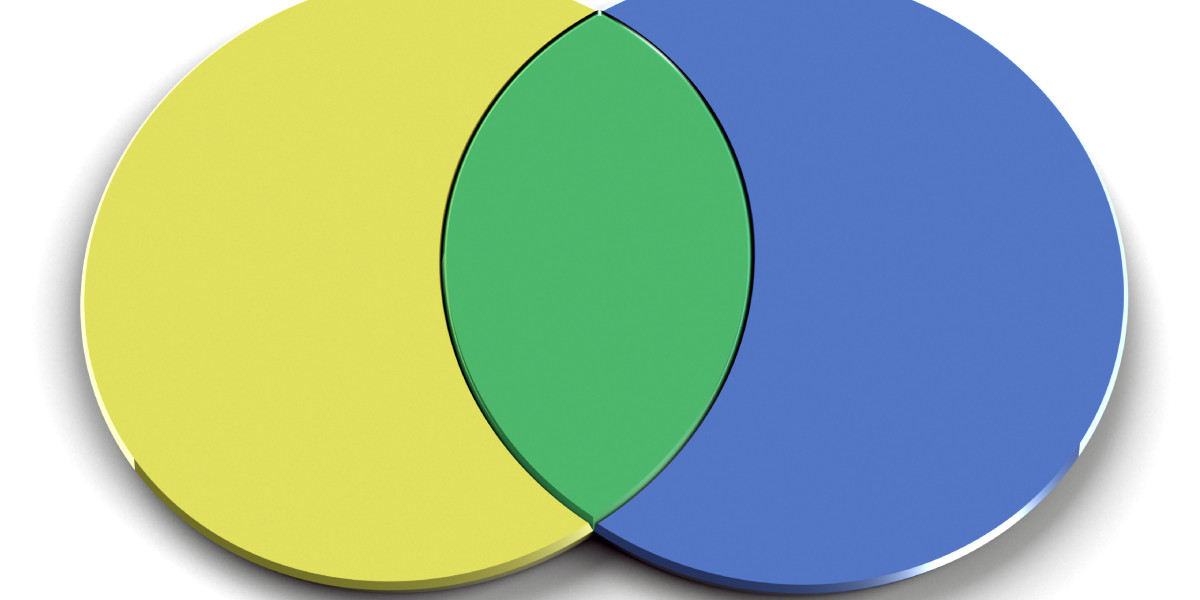

Defining the boundaries of the doctrine will likely continue to occupy litigants and courts. For now, the fundamental question can seemingly be framed in terms of Venn diagrams: Is there a truly distinct analytical space for the tort claim to occupy independent of the contract claim, or is the tort claim, instead, necessarily subsumed within the broader circle of the contract claim?

What remains to be seen is whether or not courts will allow tort claims to survive when they mostly – but perhaps not entirely – overlap with a contract claim that forms the foundation of the matter.